Federico da Montefeltro and Gubbio

Gubbio is commemorating the sixhundredth anniversary (1422-2022) of the birth of Federico da Montefeltro, the celebrated condottiere, humanist and patron of the Arts, with a large exhibition entitled Federico da Montefeltro e Gubbio. Lí è tucta el core nostro et tucta l’anima nostra. (There lies our whole heart and our whole soul).It is spread across three exhibition sites, the Palazzo Ducale, the Palazzo dei Consoli and the Diocesan Museum and is dedicated to exploring the particularly close relationship between the Duke of Urbino and this Umbrian town, which, from 1384, was under the domination of the Montefeltro family.

Gubbio is commemorating the sixhundredth anniversary (1422-2022) of the birth of Federico da Montefeltro, the celebrated condottiere, humanist and patron of the Arts, with a large exhibition entitled Federico da Montefeltro e Gubbio. Lí è tucta el core nostro et tucta l’anima nostra. (There lies our whole heart and our whole soul).It is spread across three exhibition sites, the Palazzo Ducale, the Palazzo dei Consoli and the Diocesan Museum and is dedicated to exploring the particularly close relationship between the Duke of Urbino and this Umbrian town, which, from 1384, was under the domination of the Montefeltro family.

According to his biographers,Gubbio was actually Federico’s birthplace as he was born here on 7th June 1422, in the Castle of Petroia, to be precise, and, fifty years later, Gubbio was once again the place where his longed-for male heir, (named Guidubaldo in honour of Gubbio’s Patron Saint), saw the light of day and from where, on the same occasion, his beloved second wife, Battista Sforza, departed this life. Thus it was through a succession of major life-events that Federico’s enduring links to Gubbio were forged. Gubbio was then the second most important town in the Montefeltro domains and boasted its own Palazzo Ducale. This was where he created a wood-pannelled study for himself identical to the one in Urbino, and also where the Court could reside continuing to enjoy the same comforts as in the Capital, while keeping political and military cares at a distance.

Ducal Palace

The phrase quoted in the title of the exhibition, is taken from a letter he adressed, in 1446, to the city’s body of magistrates, and offers further proof of Federico da Montefeltro’s affection for Gubbio. Moreover, the sentiment was surely reciprocated, if contemporary accounts are to be believed, as they relate that the townspeople would greet him in the street with the words ” God preserve you, Milord”. This goodwill was undoubtedly also accorded to him in consideration of the fundamental boost given to the town’s economy by the presence of the Montefeltro Court which provided a stimulus for the manufacture of goods and led to improvements in the living conditions of the citizenry.

The exhibition, curated by Francesco Paolo di Teodoro in collaboration with Lucia Bertolini, Patrizia Castelli and Fulvio Cervini, traces the most glorious period of the Montefeltro lordship of Gubbio which lasted from the birth of Federico in 1422, until the death of Guidobaldo in 1508, when the Montefeltro dynasty died out.

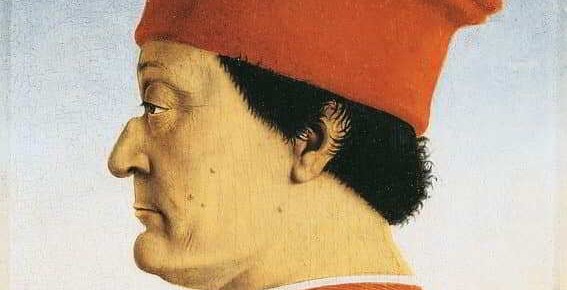

At the heart of the exhibition is the monumental Palazzo Ducale which is both a venue and an exhibit in itself. It was constructed according to Federico’s wishes by incorporating the “Corte Vecchia” (Old Court), the residence of his father, Guidantonio, which was situated just a little higher up, and the town’s original Palazzo Comunale (municipal building) slightly lower down. A selection of family portraits on display inside the Palazzo reconstructs the Duke of Urbino’s life story: there are the stone reliefs of Federico, his wife, Battista Sforza, and the man presumed to be his brother, Ottaviano Ubaldini della Carda, a miniature depicting his son, Guidubaldo, as well as a series of medals and coins, made by the most famous medallists of the quattrocento, which shed light upon the tightly-knit (but not always amicable) network of relationships connecting the Montefeltros to the other noble families who ruled over the signories throughout the whole of Italy. The sector dedicated to the Palazzo Ducale itself opens with a large group of clay tiles recovered when the roof of the building was removed and on which can still be seen traces of their original polychrome decoration featuring the Montefeltro coat-of-arms. This part of the exhibition provides detailed information regarding the history of the construction of the building and its Sienese architect, Francesco di Giorgio Martini, who undertook work for the Duke both in Gubbio and in Urbino. A number of his handwritten documents are on display, as well as copies of the most famous technical and scientific treatises on the subject from Vitruvius to Leon Battista Alberti and Piero della Francesca. The next sector deals with the external ornamentation of the Palazzo carried out by the sculptor Ambrogio Barocci and the final section is dedicated to the arts and crafts practised in Gubbio from the time of Guidantonio to that of Guidobaldo and features paintings by Ottaviano Nelli and Jacopo Bedi, the earliest representatives of fifteenth-century art in Gubbio, and also works by Bernardino di Nanni dell’Eugenia, Orlando Merlini and Sinibaldo Ibi, local artists of note during the Renaissance, as well as the small but exquisite Annunciation by Francesco di Giorgio. The craft of inlaid decoration on wood could not be overlooked and is exemplified by chests, doors and shutters from the original windows of the Palazzo, together with the huge Badalone (lectern) from the Church of San Domenico. All of these objects are suitable preparation for the visitor’s entry into the last room in this part of the exhibition, which has music as its theme. The central exhibit is the reconstruction of the Duke’s study which was disassembled in the nineteenth century and reinstalled, in the following century, in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. It has recently been restored to Gubbio in the guise of a faithful copy executed by Marcello and Vincenzo Minelli of the Bottega d’Arte in Gubbio.

Study in Gubbio

The exhibition centred in the Palazzo Ducale closes with exact replicas of the musical instruments depicted in the Study decorations together with the wooden panels by Giovanni Santi featuring the Muse musicanti (The Muses making music).

The Dioscesan Museum is host to the fascinating section of the exhibition dealing with Federico da Montefeltro’s interest in the subjects of the Quadrivium and, in particular, Mathematics, Astronomy and Astrology of which the last two were often held to be “occult Sciences”, even when understood as being fully compatible with Christian belief. The first exhibit is a detached fresco showing the Muse, Urania, holding an orb, which is her attribute. An indication of the high regard in which the two occult disciplines were held, is the fact, attested to by documentary evidence from the time, that there were two salaried astrologers at Federico’s court, Paolo da Middelburg and Jacopo da Spira, whose main function was to draw up horoscopes and astrological predictions for the current year, to which the Duke paid great attention in planning his activities both as a statesman and a condottiere. Among the many examples of such predictions on display, the one for 1482 is particularly interesting, as this was the year in which Federico da Montefeltro died and, curiously enough, Paolo da Middelburg had foretold that he would have health problems. Also on public display are astronomical and astrological treatises, as well as original examples and faithful replicas of scientific instruments from the period, including astrolabes, armillary spheres, quadrants and compasses all of which were in circulation at the Montefeltro court as documented by their frequent depiction in the marquetry decorations in the Studies in Gubbio and in Urbino. The final exhibit is composed of an interesting group of amulets, small objects intended to ward off evil, variously made out of precious metals, coral, badger fur, cristal and even wolves teeth. These were certainly in use at Federico’s court as demonstrated by their inclusion in very famous paintings such as Piero della Francesca’s Pala di Brera and the Madonna di Senigallia, as well as by the presence in the Duke’s Library of tracts dealing with the properties of stones and metals deemed suitable for the creation of effective charms and talismans.

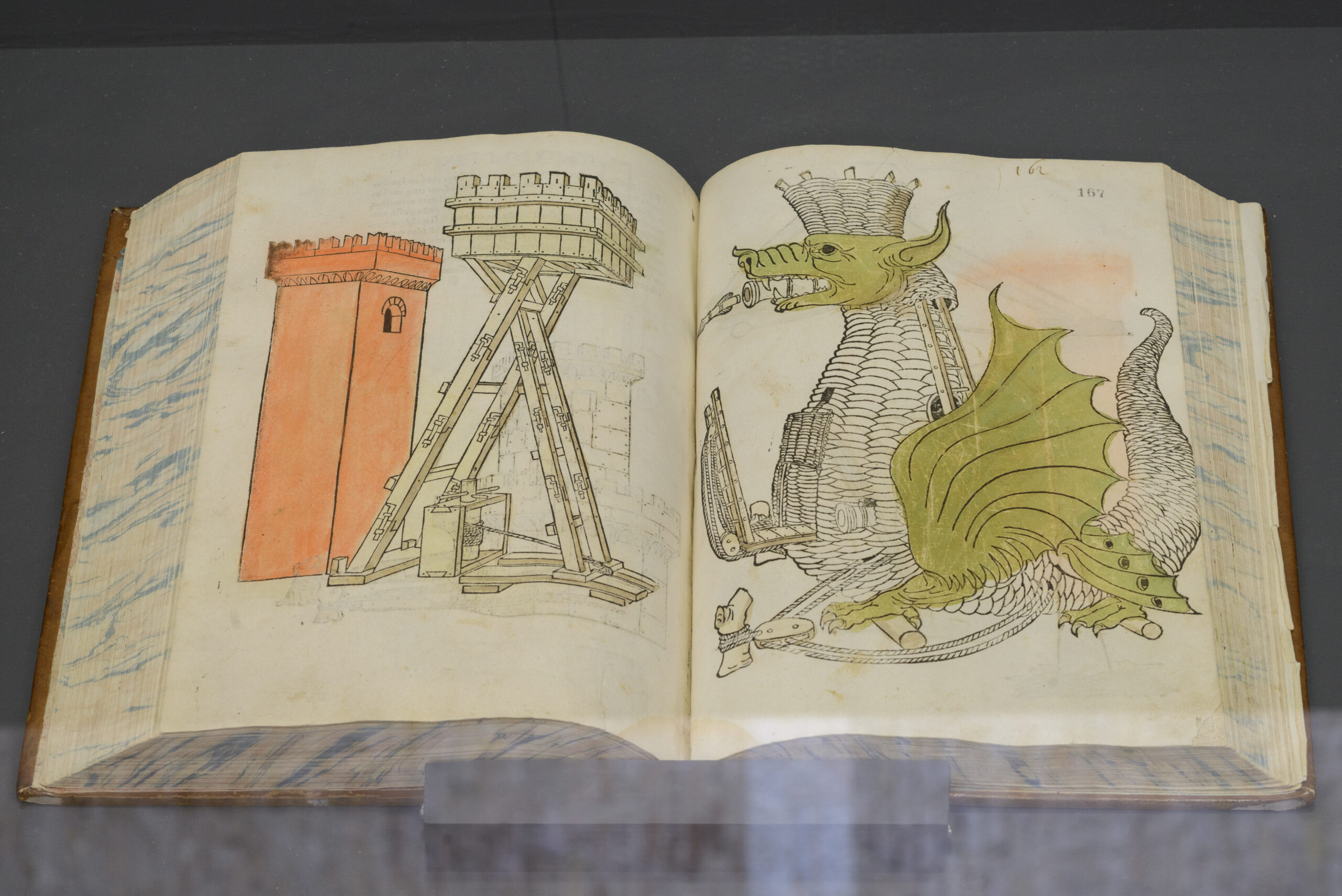

R. Valturio, De re militari

The “dual nature” of Federico da Montefeltro who was, at one and the same time, an astute warlord and a discerning humanist, is explored in the section of the exhibition located in Palazzo dei Consoli and entitled “lettere coniuncte coll’arme” ( literary and warlike pursuits in conjunction). Both of these apparently contradictory aspects were interwoven in the Duke’s character. A polymath by education, he realised that soldiering was a necessary means of asserting his own power in the context of the complex chessboard that was contemporary Italian politics, but, at the same time, he was by no means adverse to portraying himself as a princely humanist and a man-of-letters. He promoted avant-garde culture at his Court thanks also to the presence of notables such as Ottaviano Ubaldini della Carda, Vespasiano da Bisticci and his own wife, Battista Sforza all of whom played a fundamental role in the creation of Federico’s renowned Library.

The aim of the section of the exhibition in Palazzo dei Consoli is to retrace the genuine cultural interests of the Duke of Urbino, behind and beyond the mythologization in historical accounts of the period, by drawing widely on the sumptuous illustrated manuscripts – such as the Bible or the Divine Comedy – originally in the “Library”, and which now are part of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.These provide examples of both the “official” cultural content, necessary as an indication of his status, and the actual texts that Federico da Montefeltro read for pleasure. The first exhibits are some fourteenth-century codices documenting the precocious dissemination of Dante’s work in Gubbio which reveals just how fertile the town’s cultural breeding-ground already was on the threshold of the Montefeltro domination. Federico’s early education is presented through the works of his tutors, Vittorino da Feltre, who founded the pioneering Venetian school, Ca’ Zoiosa, and Guarino Veronese. In his youth and maturity, the Duke would certainly have read the “classical” authors of Italian literature, Dante and Petrarch, both of whom are represented in the exhibition by the prestigious volumes on loan from the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, the Laurenziana of the Medecis and the Nazionale in Madrid, but, of course, some “minor” works are also featured, namely the verses of Angelo Galli, the Montefeltro court poet and the collection of poems entitled Canzoniere by Alessandro Sforza, Federico’s father-in-law, who, besides being a collector of books, was also himself a poet. There is also a section with an extensive display of ancient and modern military tracts, foremost among which are the incunabulum De re militari (On Military Matters) by Roberto Valturio, a copy of which was in Federico’s Library, the De componendis cyfris (On Writing in Code) by Leon Battista Alberti, explaining how to encrypt messages, and the Liber de arte gladiatoria dimicandi (Book on the Art of Gladiatorial Combat) by Filippo Vadi, a fencing manual dedicated to Guidubaldo da Montefeltro. The book section also comprises philosophical texts, (in particular, Aristotle’s Etica Nicomachea, one of Federico’s favourite books which, according to early sources, he was wont to keep under his pillow, as well as, historical chronicles.Of fundamental importance is the one by Ser Guerriero da Gubbio, who was a notary employed by the Montefeltros, also famous for having acquired the Eugubine Tables for the town in 1456.There are also letters in the Duke’s own hand and an interesting miscellany of eulogies composed in honour of Battista Sforza after her demise.

A. Missaglia, armour

In addition to the volumes on display, there is also a section entirely dedicated to Federico as a fighting man which is opened by the impressive fifteenth-century wooden statue entitled the Guerriero dormiente (The Sleeping Soldier) by Hans Klocker and features a large array of weaponry and armour dating from the 15th and 16th centuries, none of which actually belonged to the Duke, but which are intended to convey an idea of the kinds of weapons of war in use in his day. Among these weapons there are halberds,gisarmes,estocs or thrusting swords, beautifully crafted daggers known as “sfondagiaco”( jacket piercers), as they were capable of penetrating the coat of mail, a rare example of a crossbow, made before the Cinquecento and which has survived intact to this day, as well as examples of heavy artillery such as cannons and bombards. Pieces of armour on show include backplates, breastplates, elbowpieces, helmets and crests of the kind used in battle, as well as ceremonial ones, mostly of Lombard or German fabrication, and all of these serve as introduction to the magnificent complete suits of armour on display, foremost of which is the one created by the renowned armourer, Antonio Missaglia, which closely ressembles in style the one Federico da Montefeltro is depicted as wearing on Piero della Francesca’s Pala di Brera.

A. del Verrocchio’s workshop, Battle of Pidna

The exhibition is brought to a close by two paintings on a military theme, Girolamo Genga’s Martirio di san Sebastiano (The Martyrdom of St. Sebastian) in which projectile weapons, such as lances and crossbows, can be seen, and the front panel from a wooden chest in the style of Verrocchio, depicting the Battaglia di Pidna (Battle of Pidna), with the probable contribution of his young apprentice, Leonardo, in the realisation of the landscape. The painting transforms what was an episode of ancient warfare into the representation of a large crowd of modern horse soldiers and, clearly, great delight was taken in the painstaking depiction of the exquisite armour, which seems more suitable to ceremonial use than employment on the battlefield.

How Cryptography Evolved Over The Centuries.

By Anna Bettelli, Form 4ALC, Liceo G. Mazzatinti, Gubbio

The term cryptography (from the Greek words kryptos and graphía meaning secret script), refers to the art of writing secret messages using codes or algorithms which render them unintelligible to anyone not in possession of “the key” to their interpretation. We know that encoded messages have been employed since ancient times: the first known examples were found in Egyptian hieroglyphics dating from 4500 years ago.

In the middle of the 15th century, the eminent mathematician and architect, Leon Battista Alberti, became aware of the defects in sytems of encription thanks to his statistical analysis of the language and, desirous of making them less vulnerable, he developed a pluri-alphabetical code using a number of different alphabets and substituting the letters with others (for example A became F and so forth for the remainder in alphabetical order). His Code required the construction of an instrument known as Leon Battista Alberti’s Encryption Disc.

This was formed by superimposing two concentric discs, in any material,which were connected by a pivot. On the outer disc were inscribed 24 sections containing, in order, the 20 letters of the Latin alphabet including Z, but excluding the little-used H and K, (ABCDEFGILMNOPQRSTVXZ), followed by the numbrs 1,2,3,4. On the inner, so-called, mobile disc were inscribed 24 lower-case letters in random order. The random nature of this arrangement was fundamental to ensuring greater security for the cypher key.

In the course of time, coded messages evolved, becoming ever-more complex and difficult to solve. For example, instead of leaving the invention of new encrypted codes to human beings, a machine was created in 1923, the “Enigma”, which was capable of creating, decyphering, sending and receiving encoded messages. Its prototype version consisted of three rotors (wired-up rotating discs) which, according to how they were aligned, could provide up to 150 trillion different combinations. A more modern version of it was used by the Germans in the Second World War.

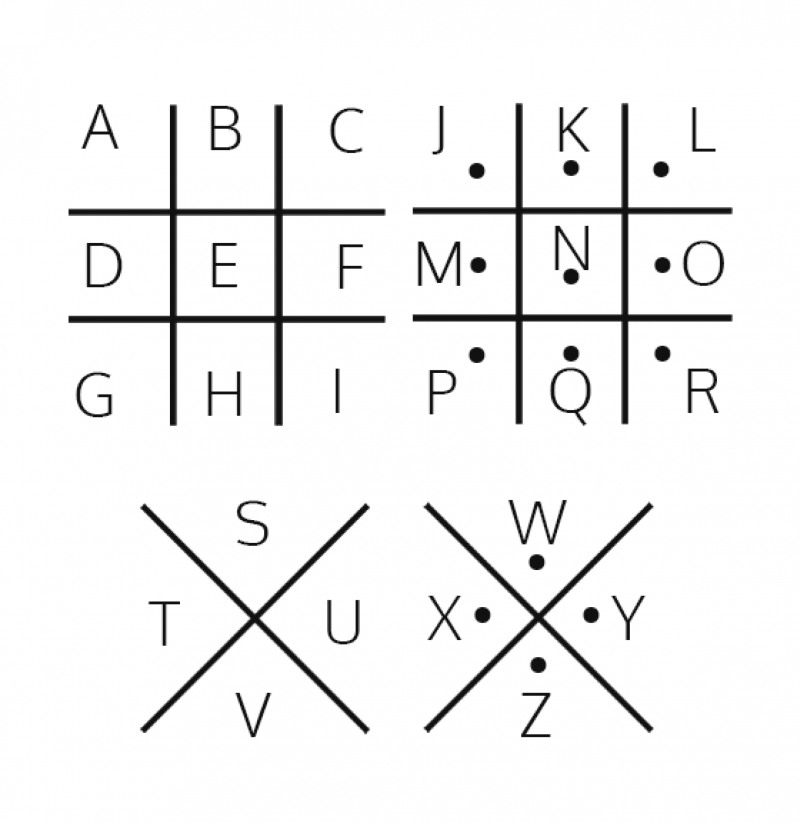

THE PIGPEN CYPHER KEY

The Pigpen Cypher Key was invented at the beginning of the 18th century and was originally used by Masonic lodges in the United States to ensure the secrecy of their accounts.Because of its simplicity, it is considered to be a weak encryption code as it is easy to crack. The Pigpen Cypher Key functions by means of the association of letters and symbols as exemplified in the photograph below.

THE FE DUX TABLET

Not everybody knows that Federico da Montefeltro, the famous Renaissance nobleman, renowned condottiere, mercenary and celebrated patron of the Arts, was born here in Gubbio, and, to be precise, on 7th June 1422, in the Castle of Petroia. He had very strong links to our town, so much so that he named his son Guidobaldo in honour of the Patron Saint, Ubaldo.The Civic Museum in Palazzo dei Consoli contains many reminders of its connection to the Dukes of Urbino, and, given that Gubbio was an integral part of the Dukedom, it is little wonder that these tokens commemorating its association with the noble family should be found in such an important building as the Palazzo dei Consoli, despite the fact that the principal family residence was the Palazzo Ducale.

In addition to the various blazons on the frescoes, and on the fountains located on the main floor of the Palazzo, there is a tablet in the Sala dell’Arengo bearing Federico’s personal emblem together with the inscription FE DUX ( Duke Federico) and some tongues of fire. These flames are also referred to as “flames of love” and were the distinguishing insignia on the livery worn by the “Accesi“, (the Ardurous Ones), the young aspirants to the brotherhood known as the Compagnia della Calza, to which Federico da Montefeltro belonged during the period he spent in Venice from 1433.

THE COMPONENTS OF A SUIT OF ARMOUR

by Elisabetta Gasparri, Form 3ALC, and Anna Betelli Form 4ALC, Liceo Mazzatinti, Gubbio

The plated suit of armour is a type of body armour made out of plates of various kinds of metals. It was a development in Europe, in the Late Middle Ages, of the plated cloak worn over a suit of chain-mail in use during the 14th century.

This use of this kind of armour was very widespread in Europe between the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th centuries. Its association with the “Medieval Knight” derives from the special version used at tournaments during the 16th century, which was highly decorative, unlike the one used in battle.

The most heavily-armoured troops were the heavy cavalry, the gendarmes and the cuirassiers while the infantry, Swiss mercenaries and the Landsknechts began to wear lighter armour, which left the lower part of the body unprotected.

Armour plated suits, as used by the nobility and cuirassiers in the Wars of Religion,became obsolete in the 17th century. After 1650, the plated suit of armour was replaced by a simple cuirass. The reason for this was the invention of the musket, a weapon that could penetrate armour more easily. The breastplate became far more important for foot soldiers as a result of the development of firearms during the latter stages of the Napoleonic Wars. The use of steel plates sewn into bullet-proof vests dates from the Second World War and these have now been replaced by versions in more modern materials such as fibre re-enforced polymers.

This is a list of the main components of a suit of armour:

- helmet

- pauncer

- backplate

- breastplate

- coat of mail

- poleyns

- pauldrons

- greaves

- Schynbalds

- gorget

- sabatons