One of the most important anniversaries of 2021 was unquestionably the 7th centenary of the death of Dante Alighieri, Italy’s premier poet.

Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri, known as Dante Alighieri, was born in Florence to a family of the minor nobility, presumably between May and June of 1265. He died in Ravenna, in exile, on the night of 13–14 September 1321.

His superlative poetry has always been a foundational component of Italian cultural identity and of the recognition of Italian culture in the world.

Dante was not “only” a man of letters, poet and author; he was also a linguist, a student of theology and philosophy, and a politician, whose writings influenced, deeply and decisively, Italian language and literature.

FOSSATO DI VICO

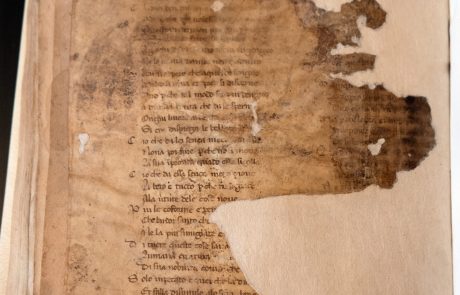

What connects Dante Alighieri to the Municipality of Fossato di Vico? A concrete nexus as fortuitous as it is unique. During the reorganization of the Municipal Historical Archive in 2004, the binding of a legal text yielded two fragments of a manuscript codex of Dante’s Divine Comedy. The fragments, which can be dated to the second half of the 14th century, reproduce cantos 4, 5, 6, and 7 of Paradiso, the third and final canticle of the Comedy.

The parchment scraps of Dante’s poem, partially superimposed on each other and not entirely readable, are written on both sides in an Italian Gothic book hand.

This important discovery is due to the practice of re-using previously written-on folios as covers for the registers and account books necessary for the work of notaries and accountants. Such re-use became common in the 16th and 17th centuries.

This precious document, preserved unrecognized for centuries in the Historical Archive of Fossato di Vico—the custodian of the community’s historical memory—restores to us, today, a witness of the great poet’s work, handing down to us the figure and the writings of the most important representative of our literary culture.

After a scrupulous restoration by the Central Institute for the Pathology of Archives and the Book (ICPAL), the fragments are exhibited in a dedicated display-case in the Municipal Antiquarium, to the great interest and curiosity of our visitors.

GUALDO TADINO

The city of Gualdo Tadino too can boast of being mentioned in the verses of the Great Poet, in Paradiso Canto XI.43–117:

“Intra Tupino e l’acqua che discende

del colle eletto dal beato Ubaldo,

fertile costa d’alto monte pende,

onde Perugia sente freddo e caldo

da Porta Sole; e di rietro le piange

per grave giogo Nocera con Gualdo”

“Between Topino’s stream and that which flows

down from the hill the blessed Ubaldo chose,

from a high peak there hangs a fertile slope;

from there Perugia feels both heat and cold

at Porta Sole, while behind it sorrow

Nocera and Gualdo under their hard yoke.” (trans. Allen Mandelbaum)

Based on this vivid reference is based the exhibition mounted in the Civic Museum of the Flea Fortress, entitled “Gualdo Tadino and Dante in Luster Glaze Ceramics.” The exhibition showcases a series of works featuring the traditional technique of ceramic luster glaze, created by Professor Alfredo Santarelli and representing scenes from Dante.

GUBBIO

There are many points of contact between Dante Alighieri and the city of Gubbio.

The first is the figure of Cante Gabrielli of Gubbio, who in the role of Podestà of Florence, condemned the poet not once but twice.

A second point of contact is in the Divine Comedy, in Paradiso XI, where Dante cites the bishop of Gubbio Ubaldo Baldassini (1085–1160), commemorating him.

The poet’s works are documented in the city begining in 1326/1327, in references found in the Teleutelogio of Ubaldo di Bastiano of Gubbio.

The earliest surviving copy of the Vita Nuova was made in Gubbio; it is preserved in the Laurentian Library (Florence).

The most prominent early Gubbian to attest to a deep knowledge of Dante’s writings is undoubtedly Bosone Novello, politician and lover of literature and the arts. Of his own literary production we have rhymes tied to the figure of Dante; a compendium of the Comedy, where Bosone deciphers the poem’s principal allegories (primarily of the Purgatorio); and a sonnet on the death of Dante.

There is a long-standing tradition that Dante, exiled from his homeland, found refuge and wrote a part of his Comedy in the Castle of Colmollaro, the final defensive outpost of Gubbio. The castle belonged to the Ghibelline family of the Raffaelli, to which Bosone belonged.